|

Eager Space | Videos by Alpha | Videos by Date | All Video Text | Support | Community | About |

|---|

The news hit the rocketry world like a Saturn V first stage with all 5 F-1 engines screaming...

President elect Trump had announced that he was choosing Inspiration 4 and Polaris Dawn astronaut Jared Isaacman to be the NASA administrator.

Along with the influence of Elon Musk in whatever role he ends up with, that would catapult NASA into the present day and there will be space puppies and space kittens for all.

The announcement generated a lot of irrational expectations, fueled by a misunderstanding of what the role of the NASA administrator is.

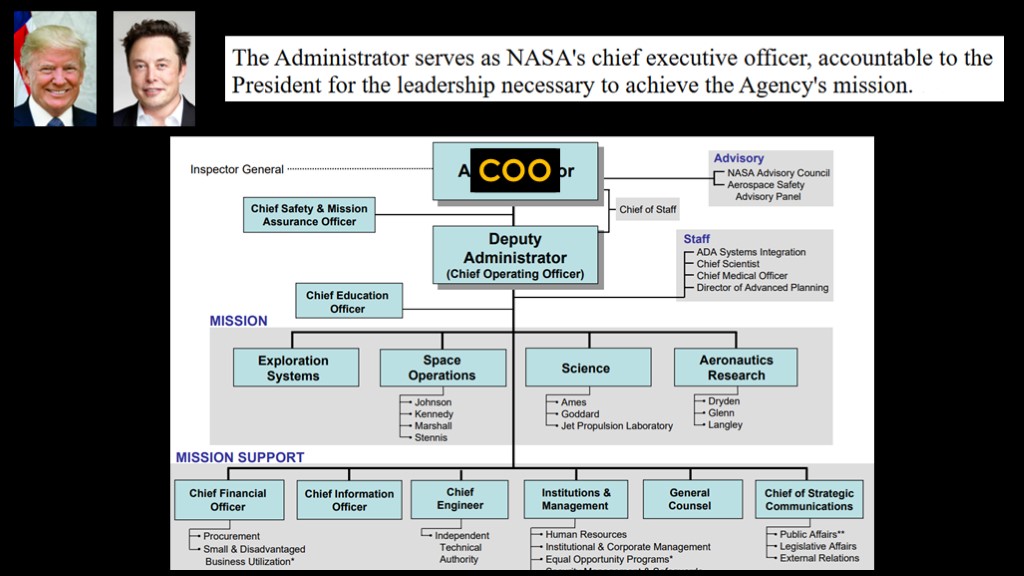

The NASA handbooks says the following about the role of the administrator:

The administrator serves as NASA's chief executive officer, accountable to the president for the leadership necessary to achieve the Agency's mission.

If we look at the NASA org chart, it looks like a corporate org chart, with the administrator on the top, and the administrator reports into the administration and ultimately to the president.

With Elon Musk driving things on the NASA side and with Trump's support, it should be easy to get things moving in a different and presumably better direction.

The problem is that the person that wrote that the administrator is the CEO doesn't understand corporate roles. The NASA administrator is not the CEO of NASA, they are the COO of NASA, the chief operating officer. It's about implementing strategies, managing teams, keeping the day-to-day operations running smoothly.

The obvious question is "if the administrator isn't the CEO, then who is?"

And the answer is that there actually isn't one.

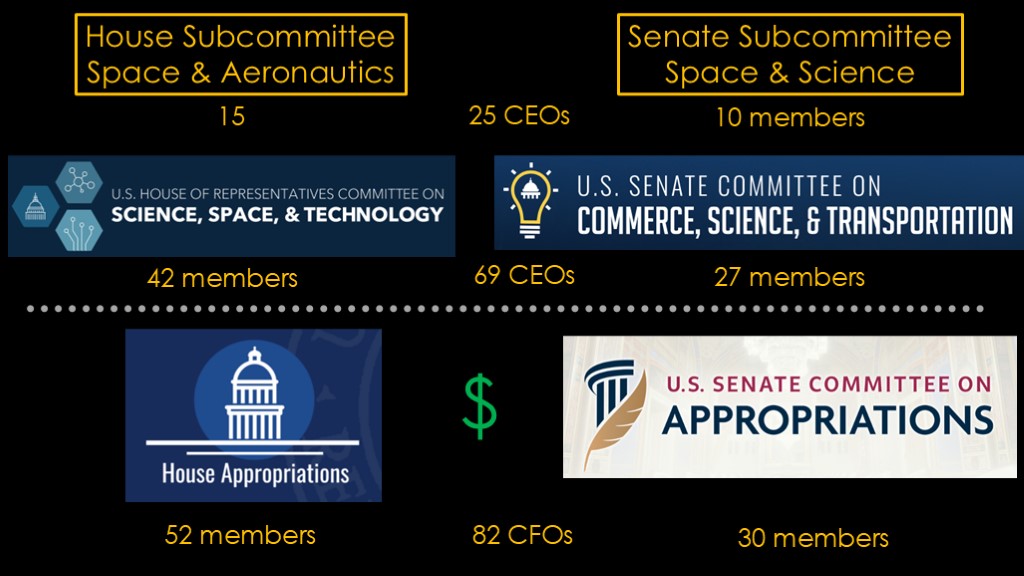

It's congress that decides what NASA does. There's the house subcommittee on space and aeronautics, which generally has 15 members, and the Senate subcommittee on space and science, which usually has about 10 members.

Put them together, and I guess you can say that NASA has 25 CEOs.

But those subcommittees report to larger committees. The house science, space, and technology committee currently has 42 members, and the senate committee on commerce, science, and transportation has 27 members. That gives us 69 CEOs.

They, as a group, decide what NASA is authorized to do - what projects they work on. But they are not in change of the money.

That is handled by the appropriations committees, with 52 members in the house and 30 members in the senate. That gives NASA 82 chief financial officers - or CFOs - who decide how much money NASA programs will receive.

The people on the appropriations committees are not the same as those on the authorization committees, and appropriations will sometimes allocate zero dollars to authorized programs or allocate a budget to programs that are not authorized.

As an example, back in 2009, president Obama commissioned a review of NASA's human spaceflight plans.

The committee found that the 9-year-old constellation program was so far behind, underfunded, and over budget that meeting any of its goals would not be possible.

He therefore removed it from the NASA budget request, and that was that.

Getting rid of Constellation canceled the shuttle-derived Ares I and Ares V rockets.

Congress immediately replaced them with a new program to create the Space Launch System. If you look closely, you might see some similarities between the two programs.

Obama's "cancellation" didn't really have the desired effect.

All NASA programs run through congress. The desires of the president and NASA administrator only matter if they can convince congress to go along with their plans.

Congress has 535 members, each with their own agenda, and it's difficult to predict how this upcoming congress will treat NASA or even if they'll spend any real time on it.

But my usual answer of "I don't know" isn't very interesting, and I'm therefore going to make some predictions based on what we know right now.

First, to set the scene, there's a big problem that NASA has been trying to avoid talking about, and that is money. NASA simply does not have the money to do all the things it wants to do.

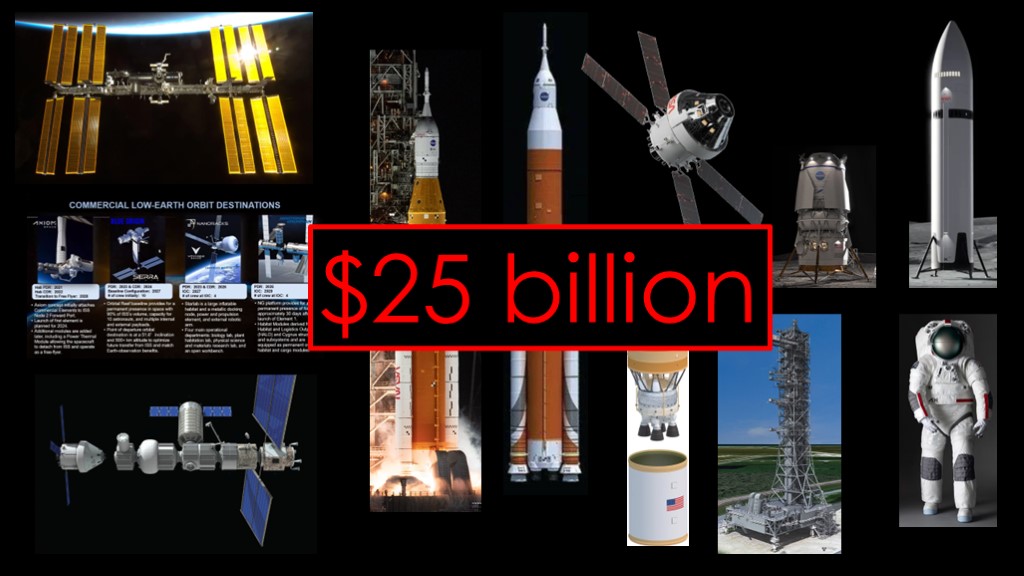

They currently spend about $4 billion a year on running ISS, $2.5 billion on SLS, and $1.2 billion on Orion.

The want to start up a commercial low earth orbit destinations program while running ISS and paying for a vehicle to deorbit it.

They want to finish developing SLS block 1B, which they estimate will cost $5 billion for the stage, including the test article for Artemis IV but not the rest of the cost of Artemis IV. The bigger rocket requires a new second stage at $2.8 billion plus a new mobile launcher for around $2.7 billion.

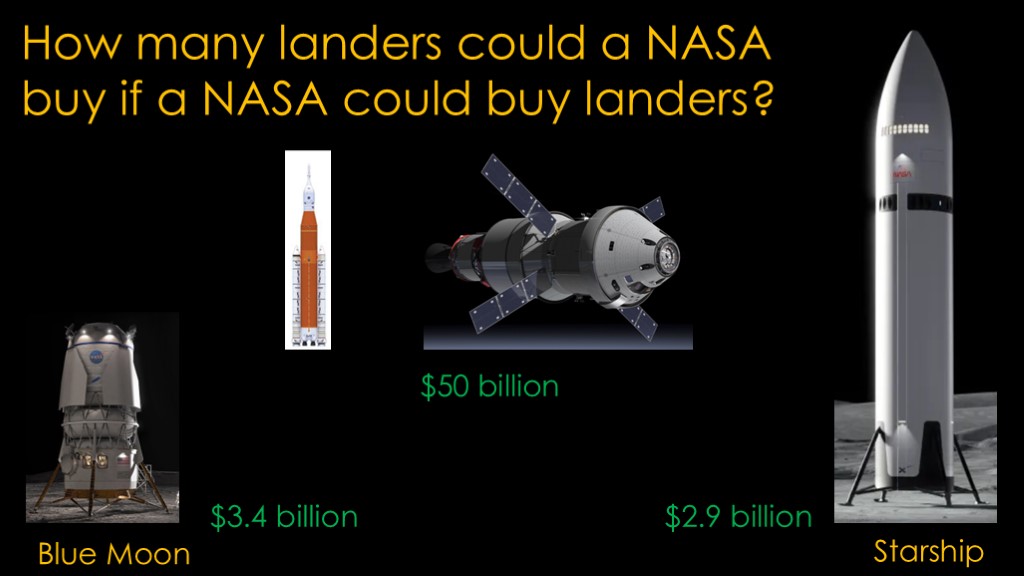

NASA needs to pay for 2 lunar landers, a relative bargain at $2.9 billion for the SpaceX starship variant, and $3.4 billion for the Blue Origin Blue Moon lander.

They need the Axiom Spacesuit, which is probably about $250 million.

And finally, they want to build the gateway space station in lunar orbit, a $5.3 billion project that would require additional flights for supply.

Those new projects are around $25 billion. If we very arbitrarily assume they will take 5 years on average, that means NASA needs at least another $5 billion a year. That would take the human side from somewhere around $11 billion to perhaps $16 billion, and you can take that number to the bank because NASA projects rarely have cost overruns.

NASA does not have that money, nor does it seem likely that congress is in the mood to give them that money. That means that NASA will have to cut some programs, which is both a problem and an opportunity...

Starting with Artemis:

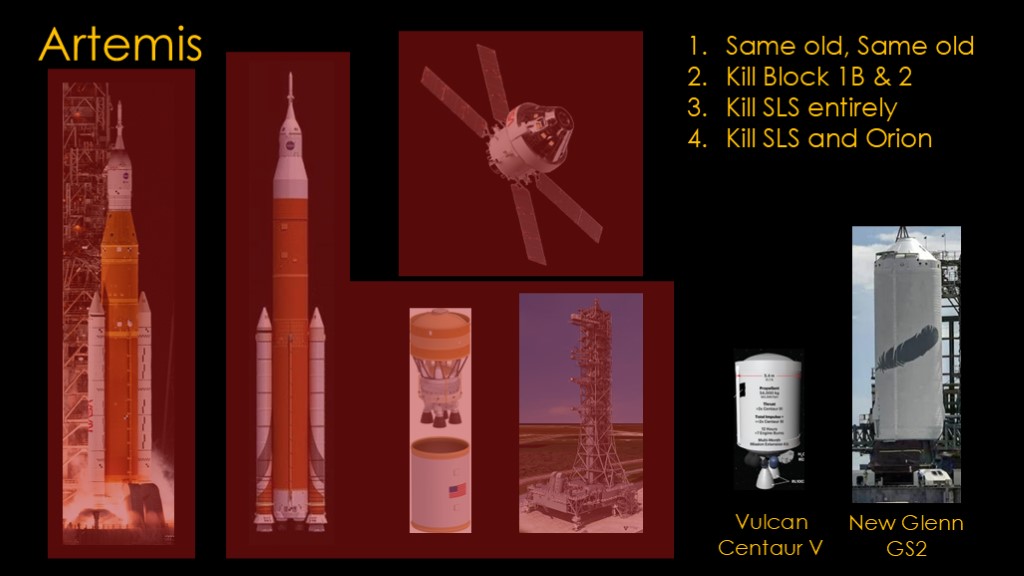

The options are

1: Keep following the plan of record, and make the schedule longer so that you can afford it.

2: Kill SLS block 1B and 2. That leaves SLS without an upper stage as the Delta IV upper stage that NASA renamed ICPS is no longer under construction. It could be replaced with the Centaur V from ULA's Vulcan rocket, which is twice the thrust of the ICPS but half the thrust of the planned exploration upper stage. It could also be replaced with a variant of the New Glenn upper stage, which is far bigger and more powerful than the exploration upper stage would be. Blue Origin might need to build a smaller version of that stage to fly on SLS.

3: Kill SLS entirely but keep orion. That saves a lot of money and complexity. You do need something to carry orion, and that could be new glenn or starship, or maybe Falcon Heavy if you do a lot of modification to the second stage to carry the extra mass.

4: Kill SLS and Orion

You might have a favorite here, but it's going to be a complex decision.

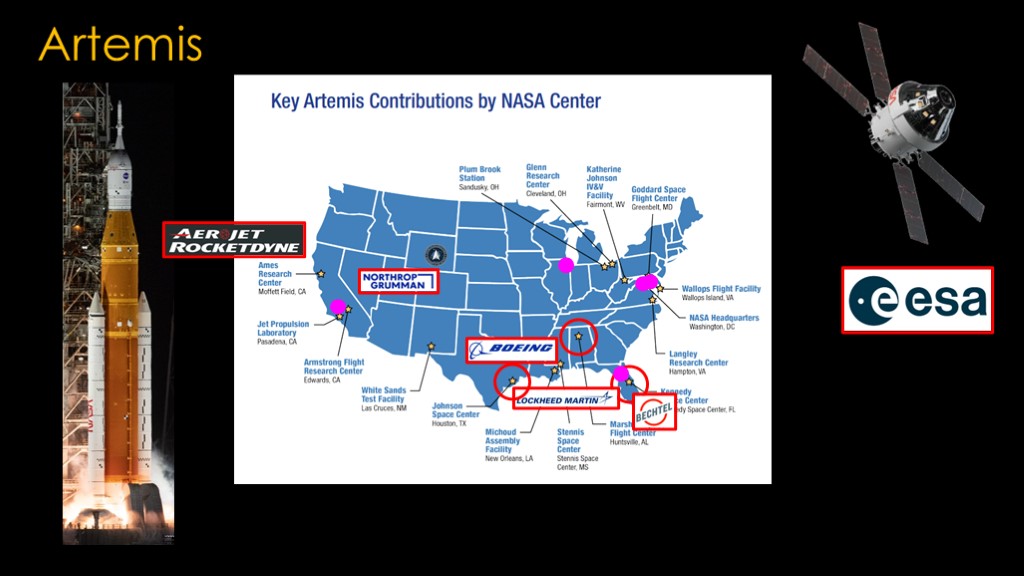

Artemis is deliberately designed to have work across all the NASA centers.

SLS is run out NASA's Marshall Space Flight Center in Huntsville, Alabama, and therefore if you want to modify or kill SLS, you need to appease the folks in Alabama.

But it's more complex than that. SLS is the only NASA rocket launching at Kennedy, so Florida cares.

Aerojet rocketdyne make the RS-25 engines for the core stage, and their factory is located in California.

Northrup Grumman makes the solid rocket boosters in Utah.

Boeing makes the core stage at NASA's Michoud assembly Facility in Louisiana.

Bechtel will make the new mobile launcher for SLS Block 1B, presumably in Florida.

Orion is also manufactured at NASA Michoud in Louisiana, and it's run out of Johnson Space Center in Texas.

And it gets more complicated. These companies have headquarters in other states, so those states care about the status quo as well.

Orion brings in the European space agency for the service module.

That means that there is going to be a lot of horse trading involved, and it's going to be complicated and messy and hard to predict. The politicians in all the states that lose business will be looking for what they can get in return.

There is supposedly a deal in the works where Alabama would be okay with SLS going away if Space Force Command moves from Colorado springs to Huntsville, a change that Trump wanted to make *anyway* and therefore is likely to happen. But is that enough to convince all the other people that cancelling SLS is the right move? That only helps Huntsville. What are you going to do so the Colorado contingent is okay with losing Space Force Command, and the Utah contingent okay with losing solid rocket boosters.

And you may have noticed that I neglected to mention the new space companies that stand to benefit if SLS goes away, your SpaceXs, your Blue Origins, your rocket labs, and others, who will all be lobbying hard to kill SLS.

This is why I generally try not to make predictions about where NASA will go. *Way* too many moving parts, and even deals that look solid can fall through because the deal is part of another bill that has issues or congress just decides to work on other things.

But, as I said, I'm going to try anyway.

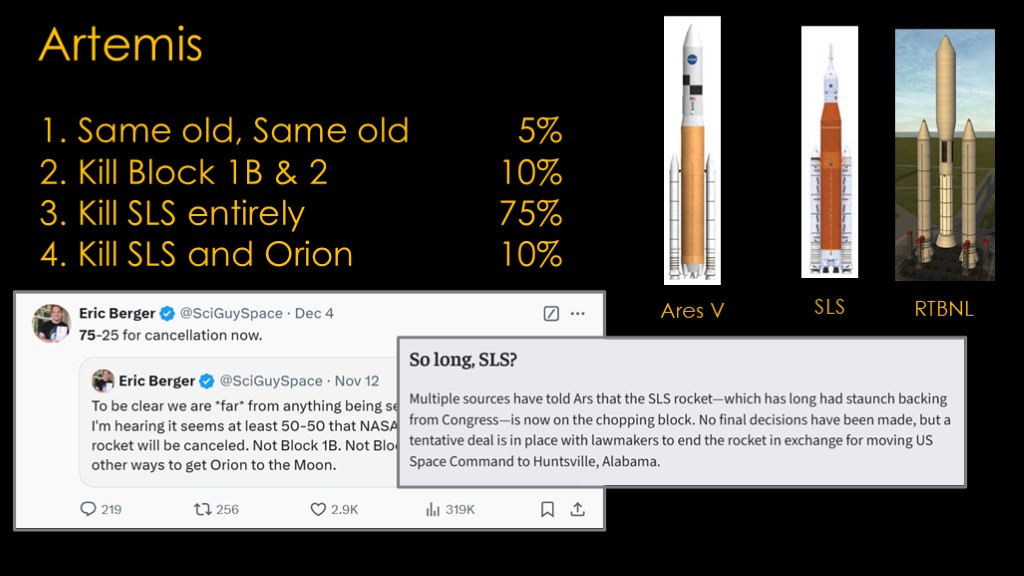

Let's put some numbers to the options.

I think the status quo option is unlikely to happen - only a 5% chance. NASA simply does not have the money to do what they want to do with their current budget, and this congress seems unlikely to give them much more.

The last option - killing both SLS and Orion - seems possible but also unlikely. Orion is a lot cheaper than SLS and has largely avoided the negative reputation that SLS has.

Which leaves us the two middle options. Back on November 12th, Eric Berger - who has great connections - posted that he is hearing that there's a 50/50 chance that option 3 is going to happen. Then on December 4th he revised that up to 75%, and the next day wrote an article about the tentative deal to move space command to Huntsville in trade for cancelling SLS.

I'm fine putting a 75% probability on option 3, and that leaves us with 10% for option 2. I can see the logic in option 2 but it invokes most of the pain of option 3 and the missing upper stage is a messy problem.

I do feel that I have to point back to what happened the last time, when Obama cancelled the Ares V and congress immediately gave us SLS, so it's possible that even if SLS is cancelled, congress will come up with a rocket to be named later.

The question of whether NASA should fund the development of two lunar landers has also been asked.

The question is a bit broken; NASA isn't funding all the development of the landers - they are paying for each company to do a test mission and a crewed mission, and they are paying a pittance because both companies have decided to fund the majority of the cost themselves. The payments in these program are structured to take place when a useful milestone has been reached, and that means NASA's big expense is keeping track of the progress of the programs, providing input, and assigning astronauts to work with the companies.

I've been a significant critic of Blue Origin in the past, but it would be great if we had two companies that could build useful deep space systems.

And given that SLS and Orion have now spent in excess of $50 billion, the landers are not the big budgetary issue.

There are also space station questions.

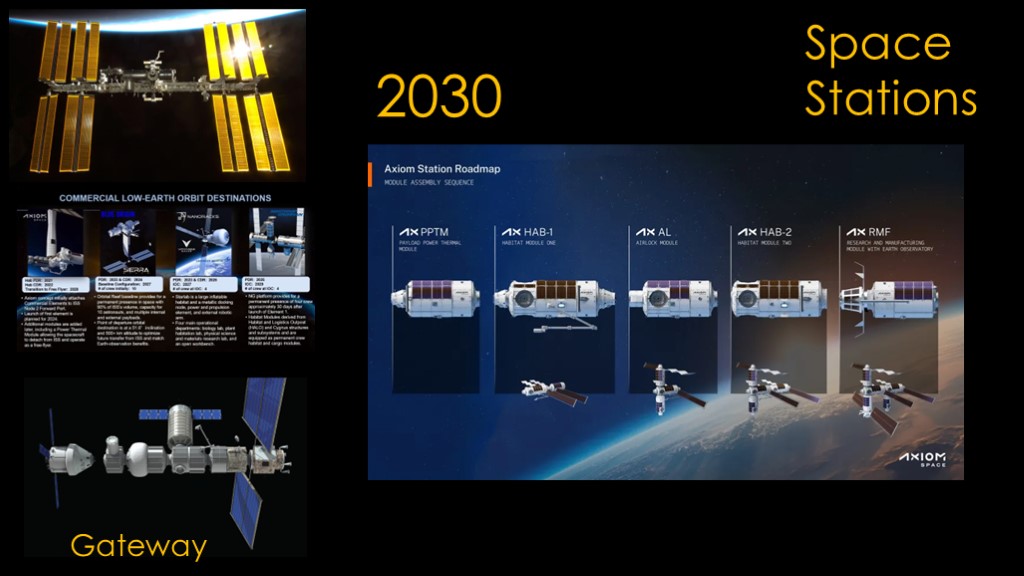

For the ISS, the question is whether the 2030 end date is going to stick, and I think this time the answer is probably yes. There will be a deorbit vehicle and the Russians have signed onto a 2030 end date. Or something could break and it could happen earlier.

There are two other big space station programs...

The commercial LEO destinations program has not gotten much love from congress or from the possible contractors, and I don't expect that big program to happen.

Which leaves us with Axiom's plans to build ISS modules that will then become a free flyer. Axiom has recently revised their plans so that their first module is capable enough to free-fly by itself. That makes it a lot easier for Axiom to finance the station, and it gives NASA a way to save some of the valuable ISS equipment by moving it to the Axiom module before it detaches.

This is a lot cheaper and simpler than the other commercial leo options, and I think it will be the one that wins out.

The final question is on gateway. If SLS is gone, gateway is gone. If SLS block 1b is gone, gateway is gone. Even if SLS survives, Gateway is a sacrificial program and I do not see it staying around.

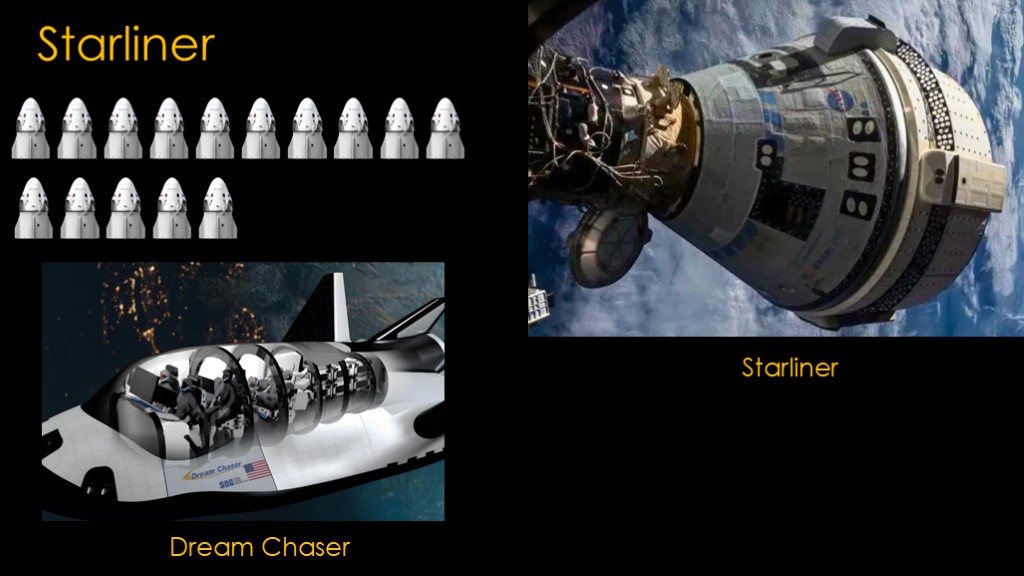

The future of starliner needs to be decided.

NASA has been highly committed to redundancy in commercial operations.

But at this point, Crew Dragon has flown 10 NASA missions and 5 commercial missions and has by all accounts been nearly flawless.

With 6 years of ISS lifetime remaining - assuming, of course, that it's not extended further - that means Boeing would need to move fast and somehow fly an operational mission in 2025, which seems unlikely.

What happens here depends more on Boeing than NASA as the big cost would be on Boeing's side, but I suspect that NASA might just say, "we're okay flying Dragon through the rest of the ISS program and we'll shift our starliner people over to work on the crewed version of Dream Chaser.

Traditionally, the administrative side of NASA has let the NASA science directorate mostly guide science and those programs do have broad support in congress. When programs blow through their budgets, congress has typically been content to hold hearings and express grave concern and then keep funding the programs anyway, but the continual cost increases of the James Webb space telescope - from the originally budgeted $1 billion up to a final $10 billion - led to real pushback from congress.

The success of JWST has helped counter that a bit, but I think both congress and the NASA administration are less likely to adopt the traditional "hands off" approach.

Which brings us to Mars Sample return.

The existing perseverance rover has been travelling around, collecting rock and atmosphere samples, and dropping them in what are hoped to be easily accessible locations.

The plan is that there will be a sample retrieval lander and ascent vehicle that will retrieve the samples and launch them into mars orbit, where an orbiter will capture them and put them in a separate spacecraft to be returned to earth.

In 2020, NASA estimated it would cost $3.6 billion and start flying in 2027

2023, the planetary science decadal group - the group that decides what NASA should focus on for the next decade - stated that mars sample return was the highest priority science mission, and said it was $5.3 billion program, roughly a 50% increase in cost over 3 years.

An independent review board concluded that MSR could not be accomplished on the timeline and budget that was available.

April 2024, SMD (science mission directorate) did a revised design with estimates from $8 to $11 billion, a 122 to 205% increase over just 4 years. Further, under this plan the first samples would not return until 2040.

At this point it was pretty clear that the existing Mars sample return architecture was dead.

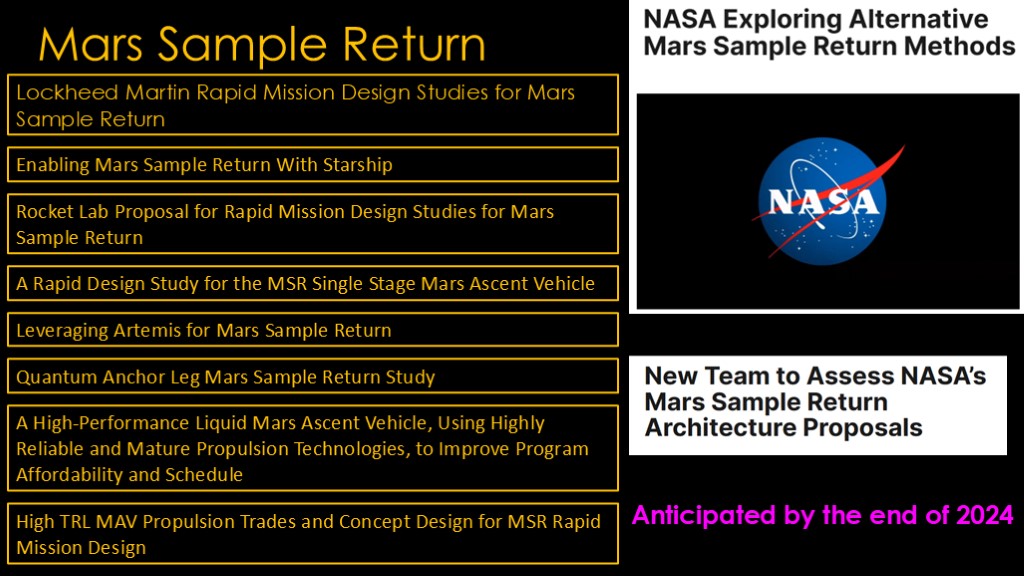

NASA remembered that they are required to use commercial solutions whenever practicable, and decided to fund a series of studies on how commercial partners might help create an architecture.

NASA has set up a team to evaluate those proposals and somehow craft a coherent architecture out of them, and their report is anticipated by the end of 2024.

As with the other programs, it's not clear who the players are in congress and it's therefore hard to predict, but I do have a few observations...

Congress is skeptical of the cost of big new programs and does not want a repeat of JWST.

Current budget estimates are not credible. When your program estimate doubles in 4 years, it's not that your early estimates were poor and your current ones are good, it's that you have no idea how to actually estimate the cost.

There's this dude who loves Mars and is planning to send his own rockets there in the next few years.

That same dude is friends with the incoming NASA administrator and president.

This one is really obvious - there is going to be a big shakeup in Mars Sample Return. That was going to happen regardless of who the administrator, president, and friends were, but the people in place means it's more likely to happen and more likely to be a significant departure from the current "plan".

And those are my predictions on what will happen at NASA with Jared Isaacman running things...

To make your own predictions, try this.